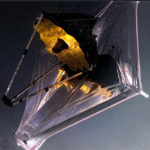

Images and spectra from the James Webb Space Telescope suggest that the first galaxies in the universe are too many or too bright compared to what astronomers expected.

Evidence is building that the first galaxies formed earlier than expected, astronomers announced at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle, Washington.

As the James Webb Space Telescope views swaths of sky spotted with distant galaxies, multiple teams have found that the earliest stellar metropolises are more mature and more numerous than expected. The results may end up changing what we know about how the first galaxies formed.

YOUNG BUT MATURE

Speaking as part of the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) collaboration, Jeyhan Kartaltepe (Rochester Institute of Technology) reported Webb’s views of galaxies when the universe was between 500 million years and 2 billion years old.

Previous studies, such as those done using the Hubble Space Telescope, had suggested that as we look back toward a younger universe, the stable rotating disks of today give way to more chaotic shapes, representative of the violent mergers that built up the first galaxies. Then again, those previous studies also had a hard time classifying the most distant ones, which looked like little more than smudges. That’s where the Webb telescope comes in.

The longer wavelengths Webb detects enable it to see farther back in time. Webb’s images are also sharper than Hubble’s, and its sensitivity greater. The CEERS group has used the new data (both images and spectra) to find 850 early galaxies, measure the distance to each one, and then tag its shape as “disk,” “spheroid,” or “irregular.”

Those classifications were not mutually exclusive. “Galaxies are complex, and they don’t necessarily fall into just one box,” Kartaltepe says. Some galaxies, for example, have both a disk and a central bulge, much like the Milky Way.

In the future, such classifications will probably be left to computers; Kartaltepe’s student, Caitlin Rose (also at RIT) is already working on convolutional neural networks and other computational methods that will eventually take over. But in the meantime, the job is still very much human: Three CEERS team members examined each of the 850 galaxies to make the classifications.

Despite their youth, the galaxies had shapes similar to those nearer to us. The percentage of disk galaxies declined only slightly in the early universe, while the fraction of those with a central bulge and those with an irregular shape stayed roughly constant over cosmological time.

Since disks are thought to form only in serene environments, in which stars can settle into a spinning skirt instead of being thrown about, their prevalence in a universe only a few percent of its current age is a bit like seeing teens when expecting toddlers. “We’re not surprised to see disk galaxies,” Kartaltepe clarifies. “I think the surprise is to see so many of them. . . . We’re really not seeing the earliest stages of galaxy formation yet.”

At the same time, she notes that yesterday’s disks are different than modern ones. “They’re not today’s Milky Way,” she notes. “They’re turbulent, they’re messy, and we need to study them more.”

AN EMBARRASSMENT OF DISTANT GALAXIES

Speaking at the same AAS press conference, Haojing Yan (University of Missouri) reported on galaxies even earlier in cosmic history. Using Webb images at multiple wavelengths, Yan found 87 distant galaxies behind the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723, their light magnified and distorted by the cluster’s gravity. The galaxies appear to date to between 200 million and 400 million years after the Big Bang (corresponding to a redshift as great as 20, in astronomer-speak).

These candidates await spectroscopic confirmation: Their redshifts are only estimates for now. But so far, spectroscopic confirmations of other galaxies have confirmed the vast majority of preliminary distances. Even if only half of Yan’s selection turn out to be nearby galaxies masquerading as distant ones, the latter number would still be unexpectedly large. “Our previously favored picture of galaxy formation in the early universe must be revised,” he says.

One of the theorists tackling this problem is Jordan Mirocha (Jet Propulsion Laboratory), who presented later in the day. “There’s either an overabundance of galaxies, or they’re much brighter than our typical models predict,” Mirocha says. He argues that multiple, interrelated factors are at work in throwing off predictions.

The first galaxies formed in still-growing dark matter halos, with ordinary hydrogen gas following the gravitational pull of the amassing dark matter particles. That inflow of matter, Mirocha suggests, might have stymied the stellar feedback that slows star formation in present-day galaxies. Yet even as the furious formation of new stars would cause early galaxies to appear bright, it would also generate dust, which in turn dims the galaxies.

Balancing all these different factors will be key to understanding how the first galaxies formed. Mirocha puts it mildly: “I think we have more to think about.”